The impressive transformation of Eldridge Cleaver: From Black Panther to Zionist and Republican conservative

The turning point in the life of the activist and writer, who died 27 years ago, occurred during his exile in Algeria, after he carried out an ambush against police in Oakland, Calif.

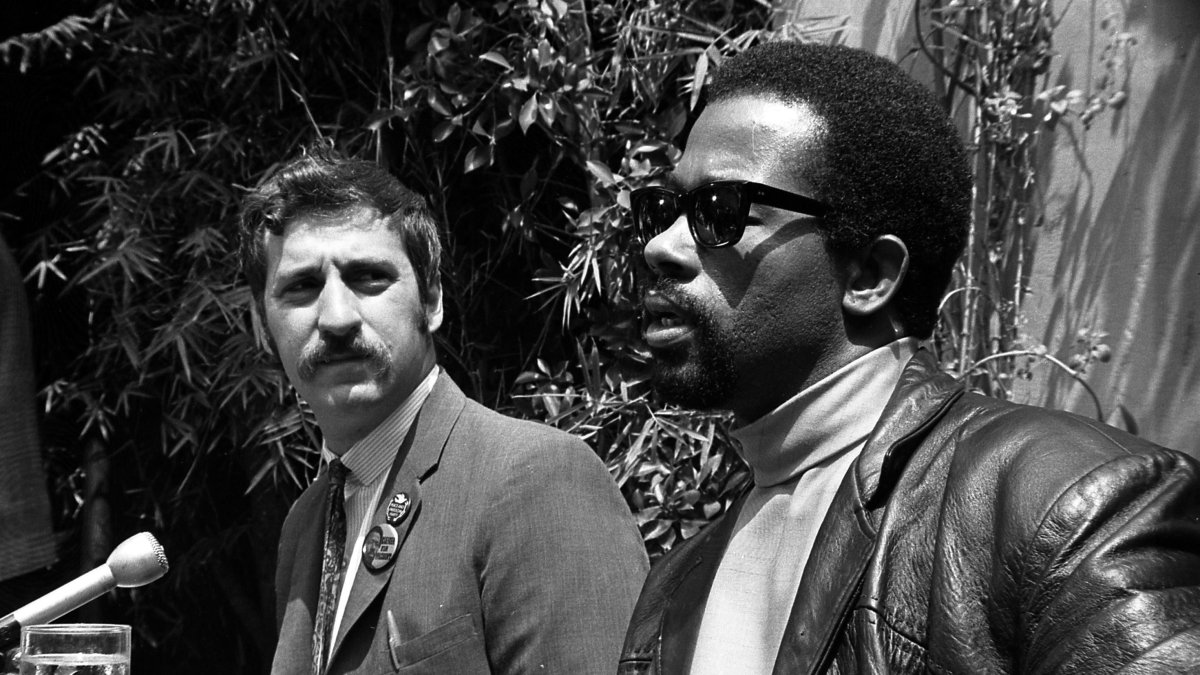

Eldridge Cleaver during his time in the Black Panthers.

May 1 marks 27 years since the death of Leroy Eldridge Cleaver (1935-1998), one of the most complex and interesting figures of the civil rights movement in the United States.

Known for his role as Minister of Information for the Black Panther Party (BPP) and author of the influential book “Soul on Ice” (1968), Cleaver went from being a symbol of African American rebellion to an advocate of Zionism and a conservative Republican. His transformation, marked by personal experiences, ideological disillusionment and a journey through exile, reflects the tensions of a turbulent era and his own search for identity.

The years in the Black Panthers

Born in Wabbaseka, Ark., Cleaver grew up in an environment marked by domestic violence and poverty. In his youth, he committed small crimes that led him to reform school and, eventually, to prison.

It was in prison that he began to write, influenced by authors such as Karl Marx, Malcolm X and Thomas Paine. His essays, published in “Soul on Ice,” catapulted him to fame as a raw and articulate voice against racism in the United States.

In 1966, Cleaver joined the newly formed Black Panther Party in Oakland, Calif., led by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. As minister of information, he became the media face of the BPP, promoting a message of armed resistance and social justice.

His incendiary rhetoric included threats against figures such as Richard Nixon. In 1968, his notoriety grew as he ran as a presidential candidate for the Peace and Freedom Party.

However, his activism put him in the crosshairs of the authorities. Following an ambush against police in Oakland in April 1968, which resulted in a shootout in which young Black Panther member Bobby Hutton was killed and two officers were wounded, Cleaver was charged with attempted murder. Rather than face trial, he fled the country, beginning an exile that took him to Cuba, Algeria and France.

JNS

‘Outrageous’ says Chicago Jewish Alliance of city’s mayor wearing keffiyeh

JNS (Jewish News Syndicate)

Exile and anti-Zionism

During his exile in Algeria, Cleaver consolidated the International Section of the BPP and established an alliance with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the terrorist group led by Yasser Arafat.

In 1969, at the Pan-African Festival of Culture in Algiers, the capital of Algeria, Cleaver met with Arafat and expressed strong support for the Palestinian cause, denouncing Zionism as a tool of U.S. imperialism.

In a 1970 statement, he asserted, "We unequivocally support the Palestinian people in their struggle against the Zionist aggressors."

This stance reflected the ideology of the BPP, which saw parallels between the African-American struggle and global anti-colonial movements. Cleaver went so far as to label Zionists as "enemies" and advocated an alliance with Palestinian Islamist terrorists.

His anti-Zionist rhetoric was part of a broader framework of Third World solidarity, influenced by Marxism-Leninism and anti-imperialism, the Wilson Center notes.

The transformation

The turning point in Cleaver's life occurred during his exile in Algeria. In his own words in the book “Soul on Fire” (1978), his perception of the Arab world changed as he witnessed what he described as the enslavement of Africans by Arabs in the country. This experience, combined with his disillusionment with communism and the internal tensions within the BPP, triggered a profound reevaluation of his beliefs.

Cleaver began to question the anti-Israel narrative he had embraced and developed an admiration for the Zionist projectas a model of national self-determination.

By 1972, Cleaver moved to Paris, where he converted to Christianity three years later, a move that marked the beginning of his move away from radicalism.

Prior to this conversion, Cleaver was essentially secular, influenced by Marxism and a brief sympathy for the Nation of Islam in the 1950s, although he never fully committed himself to any religion.

In 1975, he voluntarily returned to the United States, facing pending charges that were eventually reduced. His return was accompanied by a radical ideological transformation: Cleaver denounced the BPP, embraced conservatism and began to express support for Israel.

In a 1986 interview with Reason, he reflected on his revolutionary past with astonishment, criticizing the "anti-American ideology" of the leftist movement.

In the late 1970s, Cleaver became an advocate of Zionism, arguing that the State of Israel represented an example of resistance and sovereignty that African Americans could emulate. This stance alienated him from his former allies and brought him closer to conservative circles, including Republican figures and Jewish organizations. His support for Israel was seen as a betrayal by many in the African-American community, but Cleaver defended it as a logical evolution of his quest for justice and freedom.

Cleaver became associated with the Republican Party in the later stages of his life, adopted conservative positions, and began to align himself with Republican figures and causes. In the 1980s, he expressed support for Republican politicians, including Ronald Reagan,

The importance of combating left-wing indoctrination

Eldridge Cleaver's life is a testament to how much leftist indoctrination can harm human beings. The widespread narrative of the dichotomy of "the strong versus the weak" in racial, sexual or socioeconomic matters paralyzes people and fills them with hatred, so that instead of becoming productive individuals pursuing happiness, they become obstacles to society and to themselves, whose radically intolerant behaviors can result in widespread brutal violence and even wars.

Moreover, by framing everything in terms of "the oppressors and the oppressed," this narrative obscures the real social problems, such as true racism or true homophobia. For example, in Cleaver's case, his initial support for the Palestinian cause, based on a view of Israel as a "Zionist oppressor," prevented him from seeing the conflict with due depth until his experience in Algeria led him to question this dichotomy. Similarly, certain radical approaches, such as those in extreme feminism that label all men as violent against women or potential rapists, dilute the ability to identify and combat specific cases of domestic violence or sexual abuse. When everyone is singled out as the culprit, the real perpetrators may go unnoticed, making it difficult to combat the real ills of society.

These types of attitudes can even trigger radical reactions from the other side of the ideological map, also deriving from radicalism based on hate and intolerance but with different excuses. While supporters of both sides try to portray themselves as antagonistic to the other side, at the core, their positions and behaviors end up resembling each other more than they differ.

Cleaver managed to detox himself by learning the truth about what he had been told. His circumstances and his intellectual honesty led him to live closely and investigate everything he thought and he was able to realize that it was nonsense. There are many who still have time to remove the poison from their brains and souls for their own good and the good of society.