Sheriffs defend their agreements with ICE: "I want to help protect my community"

More than 500 counties, municipalities, and states have taken on immigration enforcement tasks, typically the responsibility of the federal government. VOZ spoke with more than twenty local authorities to learn about their motivations and the community's response.

File image of sheriff's deputies

Sheriff Richard K. Jones barely uses a Spanish dictionary, but he knows a few key words—like jefe, meaning “boss.” Clutching his hand to his chest, he says it with emphasis: “Jefe.” The word recently came in handy at his county jail, where only one out of eight or ten detained undocumented immigrants spoke English. With two he gave up entirely: of Mandarin, he knows nothing.

His county, Butler, Ohio, is one of about 250 that signed partnership agreements with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In essence, the federal agency delegates powers to local authorities, from mere paperwork to the formation of special forces with arrest capabilities.

Why: VOZ contacted 21 state and local law enforcement agencies to get the answer. Sheriff Jones': "I want to do something to help protect my community."

Just weeks ago, Jones claims that marshals arrested, in his county, a member of the MS-13 criminal gang, designated as a terrorist entity by the Administration. Rapes, robberies, murders, outrages? The list of crimes committed by undocumented immigrants in his county, he says, is long. So is the number: "2,000 crimes they have committed in four years".

But in addition to victims, he says, illegals are also the main victimizers of this imported crime. His message, which he says is backed by two decades in front of the force, is simple: "Come here legally." If not, at least in Butler, Ohio, they will be detained, prosecuted, deported.

Three models

Jones' office initialed two contracts with ICE: one to process illegal immigrants housed in its prison, another to arrest them. Ten uniformed officers in a force of 500 will be trained for the latter.

The latter, which allows arrests, is the most frequent of the three types of agreements offered by ICE. Another 241 law enforcement agencies in 26 states signed similar pacts, called the Task Force Model (Special Force Model).

The other two models allow action only on illegal immigrants already in local jails, detained for other reasons.

While both serve to streamline identification and paperwork, the so-called Warrant Service Officer program (Warrant Officer program) enables more tasks. Local officers can interrogate, take photographs and fingerprints. The one that delegates the least powers, the Jail Enforcement Model (Jail Enforcement Model), is by far the least popular:

"It isn’t a lot different than how we already interact and share information with ICE," Mike Milstead, sheriff of Minnehaha, South Dakota, explains to VOZ. After talking with the federal agency, they shook hands over the Warrant Service Officer program. He felt it "was a good fit."

Those who opted for this arrangement point out that it will streamline the bureaucracy within the confines of their prisons. "It is about ensuring that individuals who are already in custody, for serious offenses, and have been identified by ICE, are safely and lawfully transferred to federal custody," expounds Mark R. Ruppel, director of Communications for the Charleston, S.C., Sheriff's Office.

Ryan Shea, sheriff of Freeborn County, Minnesota, puts it this way:

"The program will be utilized in the Detention Center. Our Detention Staff will be serving the warrants on people who are already in custody on criminal charges. This will eliminate the need for ICE officials to drive over an hour to serve paperwork on someone who is in our custody, when our staff would be able to serve the paperwork."

"This will also eliminate the chance of someone being released by us, only to be arrested later at their home or work by ICE, causing a disruption in the community."

"We are not going out looking for immigrants," asserts Donald F Babbin Jr, police chief of Ossipee, New Hampshire. His agreement with ICE allows for arrests. But they will only be made, he stresses, "during the course of their uniformed officers normal duties."

As a former member of the federal agency, Babbin believes he has the privileged experience to bring the pact to fruition. A past that also allows him to understand, he says, "the importance of striking a balance between enforcing the law and respecting the rights and dignity of every individual."

Most of the security forces consulted by VOZ affirm that the first stage of the pact, the training of some of the local staff, has not yet begun. Or it is in its initial stages. This is the case of Babbin. So is Sheriff Patrick Callahan of Hughes County, South Dakota, who says he will undergo the training himself.

Motives and incentives

On the government side, the advantage is simple math. Turning state, municipal, urban authorities into allies allows him to multiply the agents of his deportation campaign, one of his main banners. Convinced of his appeal, he launched a campaign to seduce hundreds of potential partners.

Some local chiefs tell VOZ that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) contacted them directly. In addition to the head, the DHS targets the body: "Your Agency + Federal Law Enforcement = SAFER COMMUNITIES," reads a pamphlet addressed to agents or rank-and-file officers, providing them with arguments to convince their superiors.

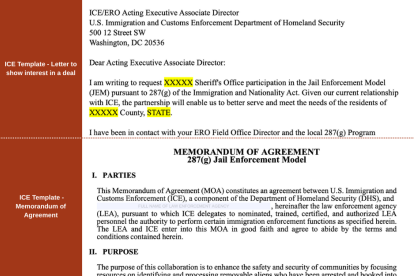

On its web, ICE even has templates for letters requesting entry into one of the agreements and memorandums of agreements, which local leaders only have to fill in with their data:

ICE Templates

In addition to free training (paid for by ICE), local forces could receive extra federal funds through a Justice Department program. The star argument, however: "Most notably, it helps you keep your community safe from potentially dangerous criminal aliens."

That is the incentive most often cited by local partners. They want, they say, to make their own community safer.

For example, as Sheriff Barry S Faile, Lancaster County, South Carolina, says, by preventing recidivism: "In removing them from our community so additional crimes will not be committed by them." Or preventing "violent offenders from slipping through jurisdictional gaps," as they say in Charleston, South Carolina.

Some more talk about a mere formalization of long-standing ties with the feds. Still others, simply, about a guide to better understand what to do with ICE detainees held in their lockups.

"I, as the Sheriff of Cowley County, Kansas, believe that there has been an influx of criminal elements that have been allowed to enter the United States, without any vetting," says Dave Falletti, one of those who cites, offhandedly, to the increase in illegal border crossings in recent years.

So does Jones, the jefe, who adds that for nearly 15 years he undertook similar collaborations with other governments, including that of Barack Obama. Until Biden came along. "They were going to different sheriffs throughout the country and getting them off ICE. So I got off before they got rid of me."

When Trump returned, he contacted the agency again.

Beyond the sheriff

The Iowa Department of Public Safety decided to put three special agents through the training required for the Task Force Model. Consulted by VOZ, it states that it seeks to "promote public safety" and that the collaboration is indistinguishable from that with other federal agencies, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) or the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

The memo, it assures, simply "formalized" the "longstanding relationship" it has with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Justice (DOJ).

Criticisms, concerns and 'fake news'

"Some concerns were raised initially—primarily around the fear that local laws might be pushed aside," shared Chief Babbin, of Ossipee. "Or that the department would begin actively seeking out undocumented immigrants." To both, he offers a single answer, "That is not the case."

While he says he understands the concern, he promises that his team "remains fully committed to serving our local community and upholding local laws." All of the 20-plus consulted respond to VOZ that their new duties will not distract them from their old ones, specific to their local area:

"The agreement will not divert our deputies or detention officers from their core responsibilities."

"We will not be diverted from our core responsibilities."

"From our conversations with ICE, we do not have reason to believe that our staff will be diverted from their core responsibilities, however we will monitor for any concerns."

"We don't take away from our duties. I'm sworn in under the Constitution of the United States as the sheriff, 'jefe', and also the state constitution. And that's my job, to enforce all laws."

Although they claim to have received few inquiries so far, local authorities say they have tried to calm concerns. From Charleston, they define it as "an ongoing conversation." "Many of the concerns come from false media reporting," says John Matz, sheriff of Winnebago County, Wisconsin.

"I do not want anyone to be afraid of calling 911 because of their immigration status," cautions Ryan Shea, sheriff of Freeborn, Minnesota. "Our deputies are not going to respond to their home and place someone under physical arrest for an immigration status if they call 911," he adds, stressing that his agreement is only valid for those already in their jails.

"It has been for the most part positive," describes the reaction of Crow Wing County, Minnesota, Sheriff Erik Klang. Of six reviews, only one was critical. Two, actually, if you add the words of the state attorney general, who publicly warned against the deals. But Klang's office, for the moment, did not get any messages.

"I’m confident that our local, state and federal partners all want the same thing," he says: "Safe communities and secure borders." "We have enough illegal alien criminals that will keep us busy with these folks for several years to come, well past the current administration."