Mexico finally approves its controversial judicial reform that attacks separation of powers

Amid strong protests, the Mexican Senate ratified the measure that makes the country the first in the world to adopt popular election of all its judges.

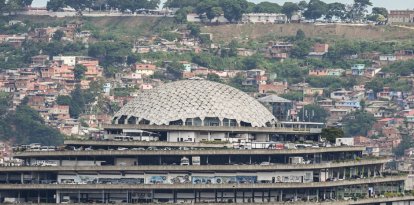

Approval of judicial reform in the Mexican Senate.

On Wednesday, Mexico's Senate approved a constitutional reform that makes the country the first in the world to adopt the election of all its judges by popular vote.

The reform was approved with 86 votes in favor, equivalent to two-thirds of the 127 senators present in the upper house, which is dominated by the ruling Morena party and its allies, and 41 votes against from opposition parties. All in the midst of strong protests that forced the temporary suspension of the session when demonstrators burst into the Chamber warning of the danger that the law poses to Democracy and Justice in the country.

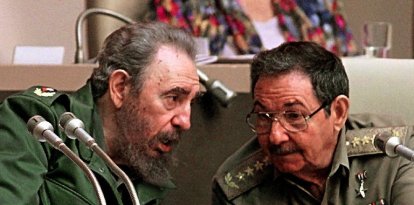

The judicial reform, promoted by leftist President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, makes Mexico the first country to elect all its judges by popular vote.

The initiative was promoted in the context of a confrontation between AMLO and the Supreme Court, which has blocked, among others, laws that expanded state participation in the energy sector and left citizen security in the hands of the military.

The constitutional reform was able to be approved thanks to the large majorities obtained by the ruling party in the elections of June 2, in which the leftist Claudia Sheinbaum was elected president.

What does the controversial constitutional reform consist of?

AMLO's judicial reform is a full frontal attack on the separation of powers on which the rule of law is based. Thus, the reform approved by the Senate contemplates the total renewal of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN), half of the circuit magistrates and judges next year.

The bill also seeks to reduce the number of Supreme Court justices from 11 to 9, reducing their term from 15 to 12 years and also seeking to establish a salary cap.

However, the most important reform, which generates most of the criticism, is the election of ministers, magistrates and judges through the popular vote; a form of election that is replicated in few countries in the world, such as Bolivia and the United States; but only partially. Mexico has gone one step further and voted that all judges be elected by this method.

Critics argue that in Mexico, a reform of this kind could directly impact the separation of powers and undermine trust in judicial institutions, weakening the rule of law and further eroding legal certainty in a country where cartels use their influence and economic power to buy favors and sway elections to their benefit.

Some of the concerns are that, if the measure is approved, up to 900 judges, magistrates and ministers could be replaced in a single election that, in addition, could coincide with the election calendar for federal deputies.

In early May, Stanford Law School's Rule of Law Impact Lab and the Mexican Bar Association warned that AMLO's proposals "constitute a direct threat to judicial independence, violate international standards and undermine democracy in Mexico."

World

Mexico's separation of powers at risk: deputies endorse AMLO's dangerous judicial reform in Commission

Emmanuel Alejandro Rondón

Diplomatic crisis with U.S. and fear of judicial surrender to drug cartels

Mexico's judicial reform brought a diplomatic clash with the United States. A few days ago, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador put "on pause" the relationship with the US ambassador in Mexico, Ken Salazar, precisely because of his criticism of the Mexican president's controversial judicial reform.

The U.S. ambassador had taken a clear position on the judicial reform, warning that the Mexican justice system could be left completely vulnerable to politicization, corruption and control by drug cartels.

In particular, Salazar mentioned that AMLO's proposed reform could "make it easier for cartels and other malign actors to take advantage of inexperienced judges with political motivations," generating, in addition, economic and political "turbulence" for years to come.