Argentina on Groundhog Day: Another March 24 fighting against ghosts

The society that was forever immunized from the military coup, has no defenses against the discourse of the Castroism of the seventies. Not even an alarm sounds when the terrorist narrative, proud of its past, educates the new generations of Argentines.

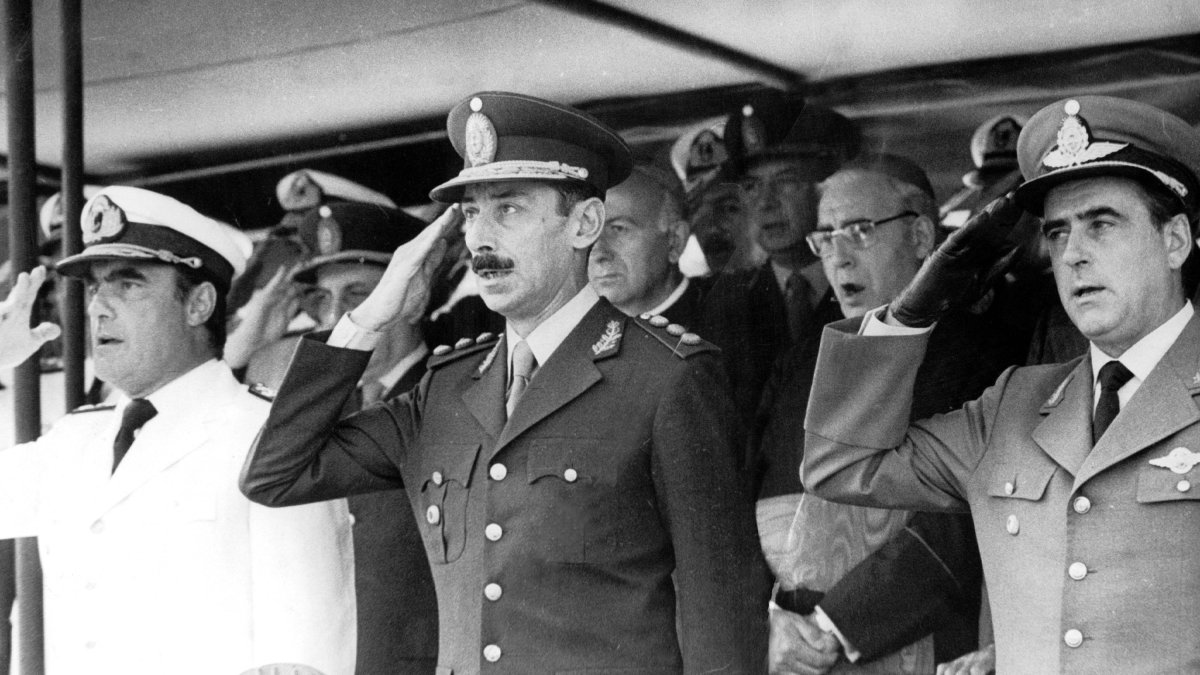

Argentine Military Junta in 1977

On December 10, 1983 the last military dictatorship known as "National Reorganization Process" ended in Argentina. The coup d'état that gave rise to it began on March 24, 1976 and occurred as the culmination of a cycle of terrorist violence by organizations that sought to implement in the country a "socialist homeland" in the image and likeness of the Cuban regime, the true puppet master of these terrorists.

When the "Process" ended and the Argentines voted again, a mold was implemented in Argentina to metabolize the events related to the violence of the seventies and the military coup that derived from it. This mold functioned as a user's manual, it set out the way in which people felt, thought, judged, remembered and thought of themselves about a period whose very existence meant a trauma. At the dawn of democracy, this could be attributed to the disturbance it meant for society to see the list of atrocities committed by the Military Juntas laid out on the table all together. The revelation of the horror that took place was a painful and suffocating shock.

The book "Nunca Más," which recounted these events, became a bestseller and the basis of argumentation for all academic, journalistic, cultural, television and symbolic production of any kind, it administered the general feeling and channeled the confusion. It is true that it was not the only material with which Argentines organized their post-dictatorship narrative, but it marked the limits within which they had to paint.

In his prologue, the writer Ernesto Sábato said: "During the 1970s Argentina was convulsed by a terror that came from both the extreme right and the extreme left, a phenomenon that has occurred in many other countries. This was the case in Italy, which for many years had to suffer the merciless action of fascist formations, the Red Brigades and similar groups. But that nation did not abandon at any time the principles of law to fight it, and it did it with absolute effectiveness, through the ordinary courts, offering the accused all the guarantees of the defense in trial; (...). It was not this way in our country: to the crimes of the terrorists, the Armed Forces responded with a terrorism infinitely worse than the one fought, because since March 24, 1976 they counted on the power and impunity of the absolute State, kidnapping, torturing and murdering thousands of human beings."

Shortly thereafter, the trial of the Military Juntas sealed forever the history of alternating coup d'états imposed since 1930. The danger of a military coup was definitively buried. No instability, no social outburst, no vindication, no politician, no external or internal condition could revive that specific ghost. Argentina has not been remotely in danger of a military coup since 1983. That may be our only achievement in decades.

However, as far as memory is concerned, a systematic and gradual rewriting of what Sábato distinguishes as the era convulsed by a terror that came from both the extreme right and the extreme left began to grow, a phenomenon that has occurred in many other countries.

There appeared a stubborn selective amnesia about the violent events that had arisen throughout the region since 1959. The members of terrorist organizations were disconnected from their military logistics, their foreign connections and the assassassinations, tortures, kidnappings and attacks committed and their explicit intentions to impose a communist dictatorship in the country. The events were also disconnected from their main driving force: the Cold War.

A basic and simplistic story was concocted, which was degraded with the passing of each version. So in the end it turned out that until February 1976 Argentina was an orchard of peace and harmony, virgin of attacks and victims, of any geopolitical influence and of any internal conflict, until a group of military men, with no other impulse than pure random evil, overthrew the then President Perón's widow. Then they set out to carry out neoliberalism in the economic field and to kill innocent people in the social field in order to reverse the workers' and students' conquests. This Manichean reductionism, which concealed the decree of President Isabel Perón ordering the repression of terrorism, had no ceiling.

The intervention of two regimes in the turbulent years that preceded the coup, the Soviet and the Cuban, was painstakingly concealed. In July 1960, Fidel Castro declared his commitment to be the "example that could turn the Andean Cordillera into the Sierra Maestra of the American continent" and sent guerrilla invasions to Panama, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua, which ended in a resounding failure. He then focused on delivering weapons and training within the island of thousands of revolutionaries from around the world eager to take up arms.

Cuba supported guerrillas in Guatemala, Colombia, Peru, Brazil, Venezuela, Argentina, Costa Rica, Chile, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Uruguay, in addition to those in Algeria, Syria, Congo, Angola and Ethiopia. In a "message to the peoples of the world" published in April 1967 by the magazine "Tricontinental," the Che Guevara formulated his famous slogan of "create two, three, many Vietnams," while traveling to the guerrilla expedition to Bolivia, a fiasco that ended on October 8, 1967 when he was captured.

Argentina was not special, but the biased history served to reinforce the ever latent demagogy, paranoia and resentment. Towards the end of the 80's and beginning of the 90's a new wave of fabricated production began to have as protagonists those who had participated in the guerrilla movements some decades before. The most prestigious journalists, politicians and thinkers amnestied the ex-terrorists, associated with them and whitewashed them. They were necessary participants for these ex-terrorists to enter the lists of deputies, university professorships, succulent public jobs and diplomatic service.

A new mantle of reverie covered Argentine society and then political parties, newspapers, professorships, TV channels and books were inaugurated and written, all of them written by those who, from Montoneros or ERP, had attacked democracy and Argentine civilians, which became an uncomfortable truth buried in oblivion. Incredibly, the society that had wisely immunized itself forever from the influence of military coupism, had not even the slightest defense against the influence of the discourse of Castroism of the seventies. Not an alarm sounded when terrorists, proud of their past, began to educate the new generations of Argentines born after the black night that Sábato narrated.

The left never rests, it does not recognize NO for an answer, it does not know how to lose. It found this vein to make its preaching survive after the return of the constitutional order and continues to shamelessly exploit it until today. The exaltation of insurgent purposes and instruments as justification, the express intention of using the last dictatorship as an ideological excuse has been a constant. Curiously, those politicians and trade unionists who encouraged the coup and even signed decrees of annihilation in the midst of democracy were never pointed out.

For the joy of Argentines, we speak of the military dictatorship that began 49 years ago and ended 42 years ago in the absolute past. However, we cannot say the same about characters, ideologies and political projects that need the "anti-dictatorship" narrative to continue plundering the country, conspiring at a regional level and indoctrinating children from an early age in schools every March 24 by repeating to them the lie of the 30,000 devised by the terrorists.

If we frankly wish to finish burying any possibility of resurgence of that tragic era we should expose the flickering flames, the mechanisms and motivations of those who attempt to go against the democratic order by stoning congresses, burning buildings, blocking roads and highways, threatening citizens, substituting land and proclaiming neo-sovereignties, corrupting equality before the law, managing social movements and associating with the most infamous dictatorships in the region, such as the Cuban or Venezuelan ones.

It remains to place Argentina in the global context to see how these phenomena are replicated in the region and stop telling the story with an eye on the country itself.

It remains to understand the molecular, chaotic paths that constitute the way in which we Argentines think of ourselves and consequently govern ourselves. It is not a mere conjunctural "story." Kirchnerism, how nefarious and intense it is, is a new phenomenon, it has a couple of decades of existence, it is not the ideologue of the "anti-imperialist" and paternalist narrative that shapes our political cosmogony. This reasoning is frivolous and inconducive because it hides an infinitely more serious phenomenon.

Coinciding with the coup alternation, Argentina embraced currents of thought that question the stages in which the liberal imprint placed the country among the richest in the world. For the charismatic leaderships of the middle of the last century to emerge, it was necessary the illiberal rhetoric disguised as anti-imperialism and all that mortar formed the minds of the children of the elites who years later would embrace the designs of the triumphant Cuban Revolution. It is not understandable without the global collectivist currents such as fascism and socialism and without its parochial nationalist components of the past.

The post-dictatorship narrative simplified all this to infantilism. Easy to digest, paranoid and narcissistic. However, this thinking was adopted by an almost absolute majority of the political arc. Oblivious, as always, to global analysis, hard data and history, the tragic evolution of recent events was once again recounted as an oligarchic conspiracy against the popular deeds.

This was the breeding ground with which those who were in a position to vote at the beginning of this century were raised and this is the reason why we have had four Kirchnerist governments. The regional political action current born in the San Pablo Forum brought to the Kirchners, criminal, corrupt and devoid of legitimacy and values characters, the narrative of the new left of which the cold lands of Santa Cruz had never heard of.

Then once again, Argentina imposed a new official truth and a new unique voice. In the five hundred spaces of memory all over the country, in all the media, in all the universities, in the INCAA, in the cultural centers, in the political profiles, in the laws, in Pakapaka and, here comes the decisive part: in the textbooks and school curricula. Not even in the times of the unfortunate little books of worship to Perón and Evita was such a massive and huge indoctrination written and spread by those who were raised with the history told by former members of guerrilla forces now reconverted into furious defenders of humanitarian values.

At this point we should ask ourselves if the seventies are really over because the presence of this symbolic corpus on education is total and dogmatic. To date, no administration in charge of education, neither in the government of Macri nor in that of Milei were in charge of reversing this indoctrinating fury that drills Argentine children and adolescents every March 24. This pro-terrorist dogma survives embedded in the entire teaching universe, that is to say: they were educated from childhood with this way of seeing the world, they were given diplomas deepening this story, they were given material to evangelize and, in case there was any milligram of freedom of thought, they were given ‘woke’ cartoons paid with the taxes of the Argentines whose standard of living has not stopped falling since the 70s.

This is how the new generations of Argentines are still being educated today. The castrochavistas are in the classrooms all over the country, they respond to a non-existent crusade like the famous Japanese who kept fighting a war that was over. And for them, the war is not over.