Who will protect the First Amendment?

The Supreme Court must rule on two state laws that could transform the internet. However, the scope could corrupt the freedoms our democracy is based on and that is more important.

(Library of Congress - Wikimedia Commons)

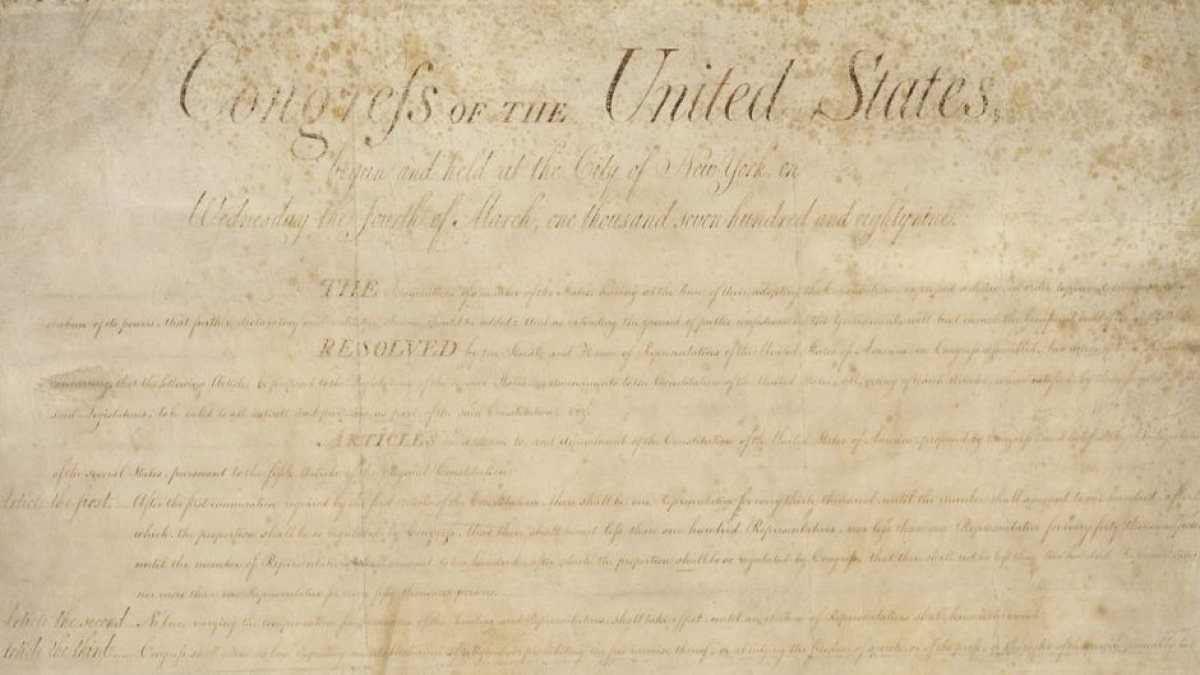

This week the U.S. Supreme Court heard two opposing arguments regarding freedom of expression. This consisted of more than four hours of debate around two state laws that regulate how tech giants control the content that appears on their sites. Each party stretches the scope of the First Amendment, corrupting the sacredness it has had for centuries. Understanding what is at stake in this battle is essential to understanding how political polarization, a crude and superficial situation, can corrode the very foundations of American democracy.

It all started after different social networks and platforms banned President Donald Trump. They blamed him for the events of January 6, 2021. Mark Zuckerberg and Jack Dorsey's companies censured Trump's opinion, along with many politicians, ordinary users and the media. State legislators in Florida and Texas reacted by passing laws to force companies to keep all posts online and not to remove political candidates from the platform. Those laws are Texas' HB 20 and Florida's SB 7072.

Two tech industry lobbying giants, NetChoice and the Computer & Communications Industry Association, filed lawsuits to block the laws from taking effect. The cases are known as Moody vs. NetChoice and NetChoice vs. Paxton and both claim that the Texas and Florida laws violate the First Amendment. They filed lawsuits to appeal these laws. The Florida law was ruled unconstitutional while the law in Texas was allowed to remain. Both cases reached the Supreme Court.

Americans have historically and largely accepted the fact that people can say whatever they want. Of course, there are rules against defamation, incitement and other exceptions, but the country has always ensured that freedom of expression is the most precious asset to protect. This has been a guiding consensus of civic life and morality. The internet has indeed changed things a lot in terms of access and production of cultural, political and journalistic content. This has, fortunately, democratized the circulation of messages. Everything good has been enhanced, as has everything bad. Nowadays, there are robots that amplify messages. There are lies that are spread innocently, and there are lies that are carefully designed for the darkest purposes. There are pressures from governments and other spaces of power, there are crimes, there is violence, and a lot of other things that have always existed in people's daily lives. The world is a hostile place, that's life.

Both laws seem very well-intentioned, but the heart of the problem lies in whether a government can force a private person to publish what they do not want.

The point is that, in the context of two key issues of the current political conversation: cancelation culture and protection against hate speech, the laws of Florida and Texas became lightning rods for the debate on freedom of expression, highlighting the tension that exists between social networks' obligations to enforce their protection and safety standards and on the other hand allow diversity of ideas and opinions. Technology companies that want to moderate their sites as they see fit argue that they are private companies and have the same rights as newspapers to decide what to print or not. They claim that the First Amendment allows private parties to publish freely without government interference or censorship.

Since its emergence, social media has moderated its content according to its own ideological framework, setting the rules for what users are allowed to say, and the government has not intervened. Section 230, a key federal law, was implemented to protect platforms from lawsuits based on published content, meaning that they decide what can be said and are not responsible for what may come of that. It also protects them from legal liability for how they choose to moderate that content.

However, the governments that passed these laws claim that social media platforms are like telephone companies, a modern agora of information exchange between citizens. They explain that a telephone company is not allowed to limit people's topics of discussion or restrict service because of the personal opinions of those on either end of the line. This argument views social networks as common transportation, a resource that everyone needs and that providers cannot deny. That is why they believe that new laws are necessary to defend users' freedom of expression. They also claim it's necessary to defend the First Amendment.

So both parties say they defend the same thing and accuse the other party of attacking the same good. The Supreme Court judges now must decide what to do with the Florida law which says that social networks cannot reject what political campaigns say, nor suppress or block content from candidates. They cannot censor a journalistic company for its content or for what it publishes. The Texas law makes it illegal for social networks to block, prohibit, remove, demonetize, deny equal access or discriminate against expression. Both allow individual users to sue social media platforms for alleged violations. Both laws seem very well-intentioned, but the heart of the problem lies in whether a government can force a private person to post something that it doesn't want to share.

The judges must decide whether to define social networks as a telephone company, which is not responsible for what people say, no matter how aberrant it may be, or as a newspaper that has editorial responsibility. Both definitions come with sophistry, truths and tricks. Many Republican leaders, including Donald Trump, have asked the Supreme Court to uphold the Texas and Florida legislation, arguing that social media companies act as public utilities and should be regulated in the same way.

A social media platform is like a telegraph, Texas Attorney General Aaron Nielson argued, defending his state's restrictions on content moderation. Instead, former U.S. Attorney General Paul Clement, speaking on behalf of NetChoice, rejected that argument and said social media platforms are like a newspaper. Neither of these analogies is entirely satisfactory. The paradox is that Clement recognizes that social networks, unlike phones that simply transmit messages, select content by exercising some kind of editorial discretion. He also knows that the Supreme Court has said that they are protected by the First Amendment. If platforms are legally prohibited from discriminating, they should not exercise those judgments.

Regardless of what the Supreme Court decides, the narrative against freedom is reaping successes and this should set off all our alarms.

In turn, Carl Szabo, general counsel at NetChoice, said that if social networks are prevented from discriminating content, "Americans across the country would be required to see lawful but awful content" such as "terrorist recruitment." Szabo omits the fact that due to ideology or government pressures, social networks censored statements about the 2020 elections or COVID-19 that later turned out to be true, while the posts of criminal material of all kinds, incitements to crime and self-mutilation and all types of discrimination and indoctrination have been allowed. Certainly, Szabo's threat is not the best argument. On the other hand, the argument that the First Amendment was intended for governments and not for private companies is. The First Amendment gives Americans the right not only to speak but to refrain from speaking, as well as to refrain from printing, financing, broadcasting, selling, or supporting the speech of others.

Protecting private companies from state intervention and control has been a banner of the right while pushing for greater interference and regulation has been a banner of the left. But in these crazy identity-driven, polarized and superficial times, many values are inverted according to political interests. In any case, freedom of expression has been attacked like never before by the left. Never before have there been so many efficient mechanisms and artifacts of social control. Progressivism has developed a twisted narrative that justifies social control to fight "misinformation." However, that right is not correctly confronting the dialectic based on the mythology of fake news, if it supports regulations that give more power to the states as a reaction to the cancellation of conservative or libertarian opinions.

The Supreme Court of the United States, based on these arguments, must make a decision that could transform the internet. It could potentially corrupt the freedoms that democracy is built on and that is more important. Regardless of what the Supreme Court decides, and it is expected to make a verdict soon, the narrative against freedom is reaping successes and this should be concerning. According to a survey conducted by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), nearly a third of Americans believe the First Amendment goes "too far" in the rights it protects. This issue made it to the Supreme Court during an election year full of ideological disputes. Experts believe that the court can rule that laws are unconstitutional, but providing a shortcut to amend them is a coin toss.

The First Amendment, the rights of property and expression and the guarantee of political diversity are a package of values taken hostage by a savage left and a right that has allowed itself to set the agenda, reacting at the wrong time. What we're seeing is an effort to misrepresent legitimate concerns about the internet's imperfections to control what we can read or say. Defending freedom cannot lead to giving more power to the government. That would be a deceptive path.