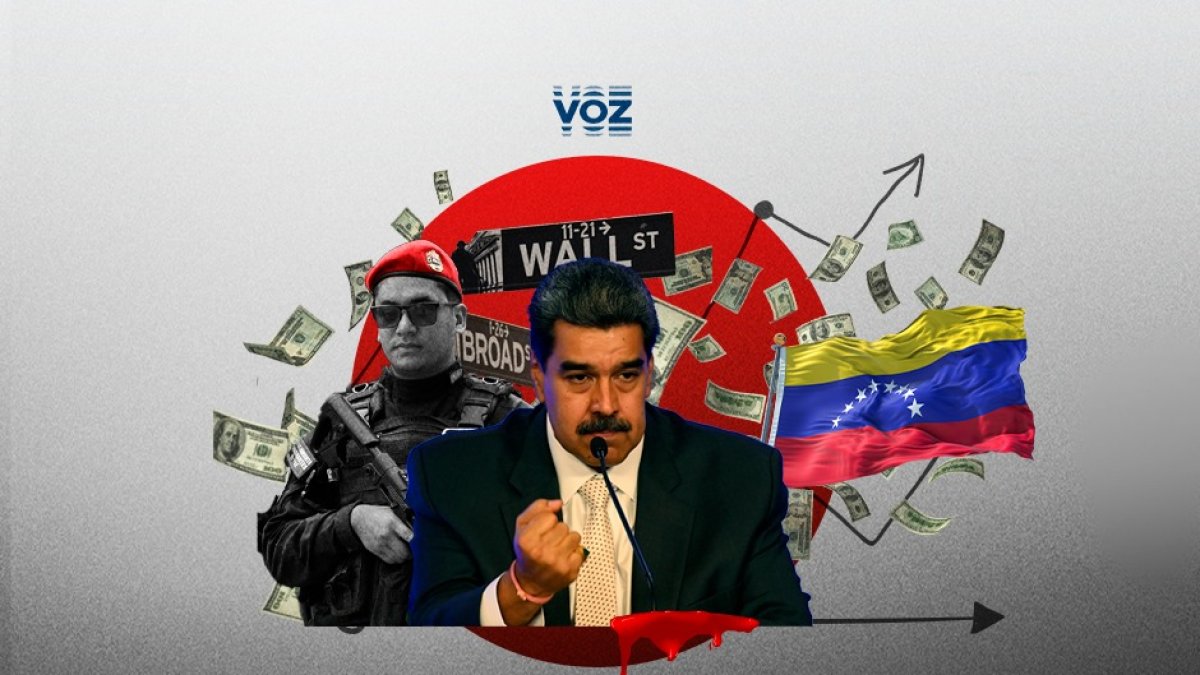

Blood for profit: How a group of Wall Street investors successfully pressured the White House to lift sanctions on Maduro

"It is a moral dilemma. Indirectly, and even unconsciously, the buyers of the bonds are going to finance Maduro."

Blood for profit: How a group of Wall Street investors successfully pressured the White House to lift sanctions on Maduro

In October of last year, within the framework of agreements between the United States and Nicolás Maduro's regime in Venezuela, The White House decided to lift several sanctions on the dictatorship. Today, the possibility of Biden reimposing sanctions is on the table due to Venezuela's breach of the agreement, but there is one that sanction is gone for good.

A group of influential and powerful Wall Street investors lobbied hard to convince the White House and the State Department that the sanction on Venezuela's debt bonds was counterproductive.

The sanction, which had been imposed by the administration of former President Donald Trump in August 2017, was a strong response to the repression and authoritarian drift that Venezuela was suffering at that time at the hands of dictator Nicolás Maduro. The measure prohibited any U.S. citizen or financial institution from participating in transactions related to Venezuelan bonds and other debt issued by the Venezuelan state.

The issuance of bonds was one of the main tools that the Chavista regime had to obtain funds. From time to time, after hiding them in national or foreign financial institutions, Venezuela would sell the bonds when it needed cash.

At the time of the sanction, several American firms owned bonds valued around $50 billion, according to The Wall Street Journal. These bonds, typically issued by the state oil company Petróleos de Venezuela (PdVSA), were extremely attractive to investors because they offered high returns and were backed by oil operations. The sanctions obviously frustrated these investors. Many managed to sell their bonds at that time.

Some of the main investors, who are still creditors of the regime today, are the Wall Street firms Fidelity Investments, T. Rowe Price and Greylock Capital. These firms did not sell at the time and, since the sanction was imposed, they have dedicated themselves to fighting the White House's policy of harassment toward the Chavista regime.

With the change of administration, the United States went from a policy of harassment to one of acceptance. Investors took the opportunity to provide State Department officials with enough information to support their narrative: by prohibiting Americans from selling and buying bonds, countries hostile to the United States, such as Russia, took the opportunity to gain ground in Latin America.

The investors provided State Department officials with "transaction records of billions of dollars in Venezuelan bond purchases by investors from Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Cyprus ... All of those places are well-known conduits for Russian money," reads a Wall Street Journal report.

Hans Humes, Greylock Capital's chief investment officer and co-chairman of the regime's creditor group that pushed for an end to the sanctions, told The Wall Street Journal that "Nobody in the U.S. government seemed to understand what market participants told them were the obvious consequences of the policy."

A man walks in front of a mural at the headquarters of Petróleos de Venezuela, PdVSA, in Caracas, in September 2023. (Photo by Miguel Zambrano / AFP)

According to a WSJ source, Fidelity Investments and T. Rowe Price each hold more than $1 billion in Venezuelan bonds. Hume's Greylock Capital holds around $1.5 billion.

In their efforts to have sanctions lifted, bondholders convinced Washington that it was likely that investors emerging from the Middle East or Cyprus, who were buying and selling Venezuelan bonds, were actually working on behalf of Russia. To support this, Wall Street investors provided U.S. officials with records and transaction documents proving that investors from the Middle East and Cyprus had also purchased Russian bonds after the White House imposed sanctions on Moscow following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Little by little, investors were putting together the narrative: Russia was accumulating a stake in Venezuelan debt, and with this it could seek an agreement to purchase Venezuelan assets in exchange for debt forgiveness. This information comes from a memo that the group of creditors sent to the United States government in 2023 obtained by The Wall Street Journal.

For Russia, Venezuela is its most important partner in Latin America. Therefore, a State Department spokesperson told WSJ, "We take seriously attempts by external actors such as Russia to expand their influence in Venezuela and take action as appropriate."

Therefore, in October of this year, after even a State Department unit assigned to Venezuelan affairs shared the concerns of investors and bondholders, The White House decided to issue General Licenses Number 31 and 9H that allows entities "to purchase certain Venezuelan sovereign bonds and PdVSA debt and equity on the secondary market."

"U.S. persons are no longer subject to the restriction that any divestment of holdings in PdVSA Securities must be to non-U.S. persons," as clarified by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC).

According to the State Department, if it had maintained sanctions on bond transactions, Russia would have continued to expand its influence over the Maduro regime and, consequently, its presence in the backyard of the United States.

However, in reality, the lifting of the sanctions allowed the group of investors and creditors to make enormous profits on the transactions. Just after the ban was lifted in October, bond prices rose from 13 cents to about 20 cents on the dollar.

The Wall Street Journal reports that investors expect the bonds to get a new boost when they become part of JPMorgan's emerging markets bond index, which could happen next month.

"We ultimately concluded that the sanctions were bad for the United States and good for our adversaries," a senior U.S. official told WSJ.

He does not mention, of course, that by lifting the ban on bond transactions, the Maduro regime can now access the international financial market more freely. The ban complicated the path for Maduro to obtain external financing.

In November of last year, several Republican senators published a statement and promoted a bill demanding Joe Biden reimpose sanctions on Maduro, considering it was the morally right thing to do.

"Human rights sanctions remain a crucial tool to help Venezuelans who continue to suffer under Maduro’s criminal regime. We have a moral duty to ensure that this narco-regime is held accountable for its countless crimes and that sanctions remain in place," said Republican Sen. Marco Rubio.

Republican Sen. Rick Scott said, "Time after time we’ve seen President Joe Biden appease murderous dictators like Maduro by lifting sanctions, allowing millions of dollars to fuel his dangerous regime and further destabilize the region."

Scott and Rubio were also joined by Senators Ted Cruz and Bill Hagerty in supporting the Venezuelan Human Rights Defense and Civil Society Reauthorization Act.

When asked about the sanctions, Joseph Humire, expert in security and transnational crime, analyst for The Heritage Foundation and director of The Secure and Free Society, told Voz Media that "lifting sanctions without any guarantee that there will be a change in the regime's behavior is a perverse incentive. You are encouraging bad behavior. ... You sanctioned them because their behavior was wrong, and today not only is it not better, but it has gotten worse."

On lifting of the ban on buying and selling debt bonds, Humire said that the license allows Venezuela "to legitimize the dirty money that [it] manages with its debt. The illicit economy in Venezuela is mixed with the formal economy. The debt and bonds they issue do not differentiate between the circulation of illegal money."

For the security and crime expert, the money that comes from Venezuela will inevitably contaminate the United States financial system.

Finally, Humire considers that, even unintentionally, American investors end up indirectly financing the repressive dictatorship of Nicolás Maduro by trading in Venezuelan debt bonds.

"When you legitimize a financial system of an autocratic country, which is linked to organized crime, when you insert them into the market, by extension you are legitimizing it," he said.

The sanctions, Humire argues, were designed to prevent dirty money from entering the formal market and the regime from obtaining financing.

"It is a moral dilemma. Indirectly, and even unconsciously, the buyers of the bonds are going to finance Maduro," said Joseph Humire.

In recent weeks, the Venezuelan dictatorship has notably intensified its repression, ordering the capture of several members from the team of opposition leader María Corina Machado. A few days ago, the regime also arrested human rights activist Rocío San Miguel. After she was missing for more than four days, the regime sentenced San Miguel to prison on charges of terrorism.

San Miguel will spend her days in the largest torture center in Latin America: Helicoide.