Justice Thomas takes aim at Jack Smith, claims his appointment was unconstitutional

The Supreme Court justice filed a concurring opinion in the ruling on presidential immunity that may pave the way for Judge Aileen Cannon in Florida.

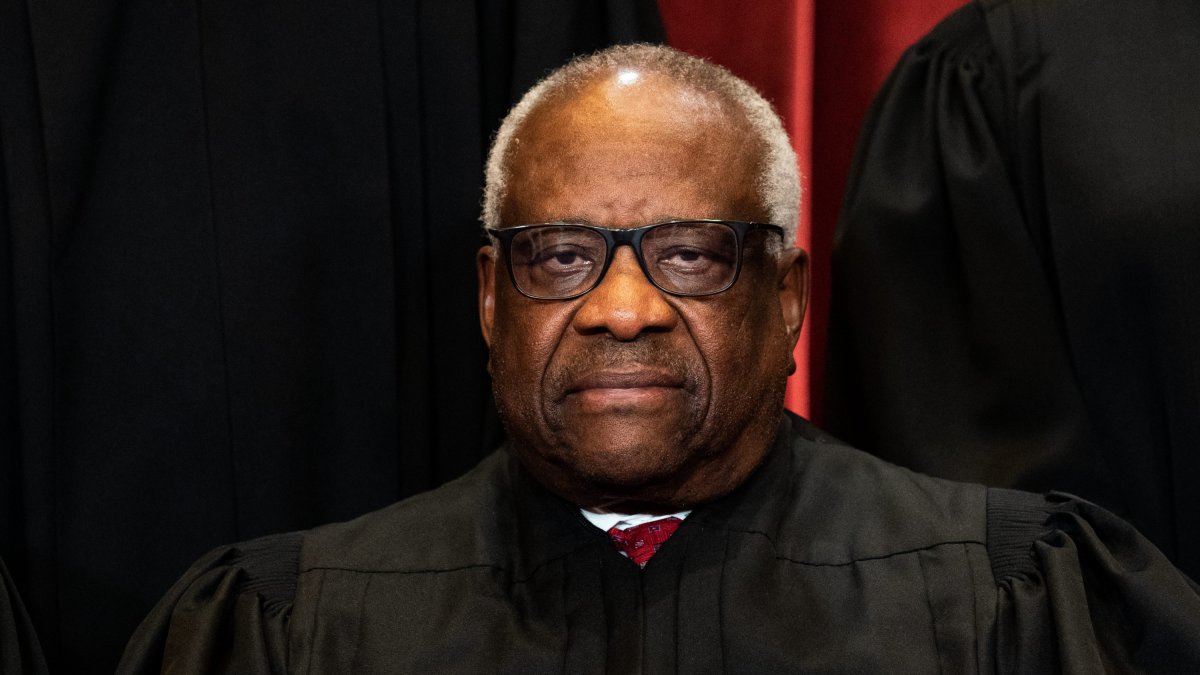

Official image of Justice Clarence Thomas.

The Supreme Court ruling dealt a severe blow to the aspirations of special counsel Jack Smith. Not only because the court's endorsement of Donald Trump's presidential immunity makes the Jan. 6 case against him an uphill battle, but Smith's own position has been seriously questioned by the court.

In a concurring opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas noted that Smith's appointment, in his mind, was "unconstitutional" and the current special counsel should no longer hold that position. In the nine-page opinion, Thomas points out that this is a serious situation that must be addressed in lower courts.

Thus, Thomas questions whether Smith's own appointment amounts to a violation of the Appointments Clause of the Constitution. He also questions whether "any office for the Special Counsel has been 'established by Law,' as the Constitution requires."

According to Thomas, the first thing to analyze is whether Smith's appointment complies with the provisions of the Appointments Clause. This indicates that "Officers of the United States" must be nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate, while giving Congress the power to create specific offices: "By requiring that Congress create federal offices 'by Law,' the Constitution imposes an important check against the President — he cannot create offices at his pleasure." Thus, in this case:

"If there is no law establishing the office that the Special Counsel occupies, then he cannot proceed with this prosecution. A private citizen cannot criminally prosecute anyone, let alone a former President."

To the contrary, Thomas points out that Smith was hired by Garland directly as a private citizen. Yet he has been given constitutional powers that do not belong to a mere employee of the country's attorney general: "If this unprecedented prosecution is to proceed, it must be conducted by someone duly authorized to do so by the American people," especially if it is to bring a former president to trial, something that has never happened before.

A measure from the founding fathers to check presidents' power

In fact, Justice Thomas points out that the idea of the founding fathers with this provision was precisely to avoid political persecutions from presidents taking advantage of their office against rivals or dissenting citizens:

"By keeping the ability to create offices out of the President’s hands, the Founders ensured that no President could unilaterally create an army of officer positions to then fill with his supporters. Instead, our Constitution leaves it in the hands of the people’s elected representatives to determine whether new executive offices should exist."

Second, Thomas analyzed whether the office of special counsel was properly established. The justice noted, "It is difficult to see how the Special Counsel has an office 'established by Law,' as required by the Constitution. When the Attorney General appointed the Special Counsel, he did not identify any statute that clearly creates such an office. ... Nor did he rely on a statute granting him the authority to appoint officers as he deems fit, as the heads of some other agencies have. Instead, the Attorney General relied upon several statutes of a general nature."

'Invalid' appointment

Thus, "Even if the Special Counsel has a valid office, questions remain as to whether the Attorney General filled that office in compliance with the Appointments Clause. ... For example, it must be determined whether the Special Counsel is a principal or inferior officer. If the former, his appointment is invalid because the Special Counsel was not nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate, as principal officers must be. ... Even if he is an inferior officer, the Attorney General could appoint him without Presidential nomination and senatorial confirmation only if 'Congress . . . by law vest[ed] the Appointment' in the Attorney General as a 'Hea[d] of Department.' ... So, the Special Counsel’s appointment is invalid unless a statute created the Special Counsel’s office and gave the Attorney General the power to fill it 'by Law.'"

Moreover, Thomas indicated that his position is not something to be taken lightly: "Whether the Special Counsel’s office was 'established by Law' is not a trifling technicality. If Congress has not reached a consensus that a particular office should exist, the Executive lacks the power to unilaterally create and then fill that office." Therefore, Justice Thomas urged that these questions be resolved as expeditiously as possible: "Those questions must be answered before this prosecution can proceed. We must respect the Constitution’s separation of powers in all its forms, else we risk rendering its protection of liberty a parchment guarantee."