When Illegitimacy Breaks the Rules: Why the US Move in Venezuela Isn’t What Critics Claim

After years of watching fake elections, managed negotiations, and ritualized disappointment, Venezuela is confronting something unfamiliar: the end of guaranteed impunity. Trump has made clear he intends to supervise the transition.

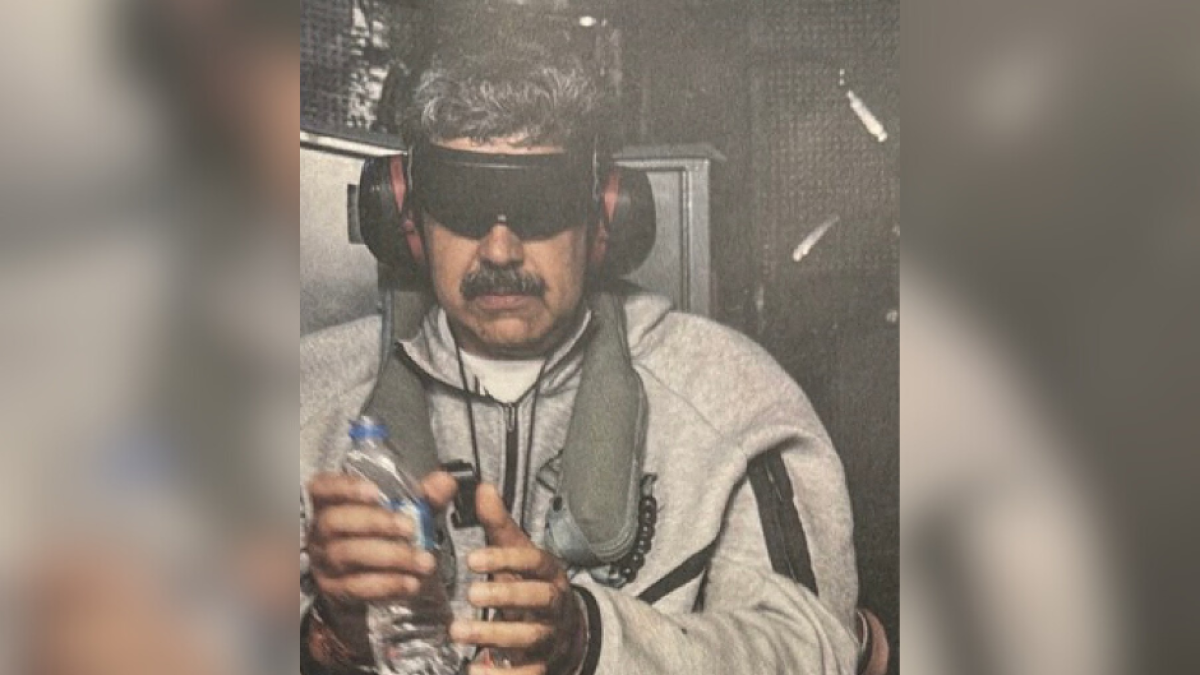

Maduro arrested

More than a century ago, Venezuela was subjected to a European naval blockade designed to force repayment of sovereign debt. The episode was humiliating, but instructive. Weak institutions invite external pressure. That crisis helped inspire Latin America’s Drago Doctrine, which argued that debt could not justify armed intervention—and it coincided with the United States’ emergence as the ultimate referee of hemispheric order.

That history matters because Venezuela is once again at the center of a geopolitical rupture. And once again, the United States is shaping the outcome. The difference this time is not tactics, but justification.

On January 3, US forces captured Nicolás Maduro and removed him from power. Predictably, critics rushed to denounce the move as illegal, imperial, and destabilizing. But those critiques depend on a claim that no longer withstands scrutiny: that Maduro was a legitimate head of state entitled to the full protection of sovereignty.

International law is built to regulate relations among governments that govern. It was never designed to provide permanent immunity to leaders who lose elections, dismantle institutions, and rule through force.

In 2024, Maduro failed the most basic test of legitimacy when he lost the presidential election to Edmundo González and refused to leave office.

González went into exile. Maduro stayed, propped up by a captured judiciary, a politicized military, and security services designed to survive the vote.

That distinction is not academic. It fundamentally alters how the world evaluates claims of sovereignty.

Long before January 3, Washington had already moved Maduro out of the category of “normal counterpart.” In 2020, U.S. authorities indicted him on narco-terrorism charges, framing him not merely as an authoritarian ruler, but as the head of a criminal enterprise embedded in the state. That legal and political architecture did not appear overnight. The operation against Maduro was not a rupture—it was the execution of a framework years in the making.

Public reaction reflects this reality. EyesOver’s analysis of U.S. discourse shows that even before the operation, Venezuela was overwhelmingly viewed through the lenses of economic collapse and authoritarian governance. Sympathy existed, but it was directed at Venezuelans—not at the regime. Maduro himself was singled out as the focal point of repression, corruption, and illicit networks. In the American public mind, he was already detached from the idea of legitimate sovereignty.

That helps explain why the operation immediately shifted the conversation. The debate did not center on whether Maduro deserved protection. It centered on American power—its scope, its risks, and its intent. Supporters framed the move as regime accountability and anti-cartel enforcement.

Critics warned of escalation and executive overreach. But notably absent was any serious defense of Maduro as a lawful ruler wronged by foreign aggression.

President Trump’s blunt declaration that the United States would “run” Venezuela during a transition shocked diplomatic sensibilities. But it also revealed something foreign policy professionals understand, even when they prefer not to say it aloud: states act on interests, not sentiment.

Trump did not obscure the economic dimension. He openly discussed rebuilding Venezuela’s oil infrastructure, restoring production, and involving U.S. firms in stabilizing a collapsed energy sector. That candor drew outrage—but it also stripped away hypocrisy. Venezuela possesses the world’s largest proven crude reserves. A country with that level of strategic wealth and institutional collapse was never going to be left to drift. Acknowledging national interest does not delegitimize action. It makes it transparent.

The most controversial signal, however, was Trump’s openness to working through Delcy Rodríguez rather than relying on Venezuela’s traditional opposition. To critics, this sounded like betrayal. In practice, it reflects a hard lesson learned over the past decade.

Symbolic legitimacy without control of territory, institutions, or security forces does not produce transitions—it produces stalemates.

That is also why the recent meeting between María Corina Machado and Donald Trump matters—and why it has been widely misunderstood. The meeting was not a reversal of Trump’s pragmatism, but a clarification of it. Machado represents moral clarity, electoral legitimacy, and the political mandate that Maduro tried to erase in 2024. By engaging her directly, Trump signaled that recognizing power realities does not mean abandoning democratic . It means sequencing them. Machado offers the democratic endpoint; Trump is focused on enforcing the conditions that make that endpoint possible. The message was implicit but unmistakable: legitimacy will be restored, but it will not be restored symbolically. It will be restored through leverage, control, and a transition that cannot be vetoed by the same institutions that nullified the last election.

Venezuela’s problem has never been a lack of opposition figures. It is a lack of enforceable power. Any transition that ignores the internal machinery of the state—courts, ministries, armed forces—risks collapsing into chaos or allowing the same system to reconstitute itself under new branding. Trump’s approach signals a preference for a managed handover rooted in control, not slogans: cooperate and there is an exit; resist and there are consequences.

The Venezuelan diaspora understands this instinctively. Celebrations abroad framed Maduro’s removal as liberation, translating years of repression and forced migration into language that resonated with U.S. audiences. Yet beneath the relief sits anxiety—about retaliation, stability, and whether this moment leads to real change or another reset of the same machine. That anxiety is justified.

Maduro was not the regime. He was his face. Chavismo still controls courts, governorships, security forces, and economic networks.

Removing one man does not dismantle a structure. But it does change internal math. Fear reshapes negotiations. It fractures certainties.

That is why this moment matters.

After years of watching fake elections, managed negotiations, and ritualized disappointment, Venezuela is confronting something unfamiliar: the end of guaranteed impunity. Trump has made clear he intends to supervise the transition. That is not ideal. But Venezuela is not in a normal political moment. The alternative is letting the same system reset itself—again—and calling it progress.

If illegitimacy means anything, it must mean this: sovereignty has limits. And when those limits are crossed, consequences follow.

Daniel Tirado, Research Analyst at EyesOver.