"Oregon turned into the Wild West": Decriminalizing drugs was an epic failure

The first state to remove penalties for possession is about to become the first to re-criminalize them. Experts say we should learn from Oregon's mistakes.

(AFP)

"It was something that shouldn't have been done, it caused more harm than good." That's what the polls show that people think about the decriminalization of hard drugs in Oregon, known as Measure 110 (officially called the Drug Addict Treatment and Recovery Act). A homeless fentanyl addict said, "[Oregon] turned into the Wild West."

That is one of the testimonies Kevin Dahlgren heard. He walks the streets of the Beaver State talking to those who live there to get an idea about the problems that come with homelessness. In the video, Dahlgren says, "Personally, I have never found more bodies in my life than I have in last year." He interviewed someone who said, "Yeah, I've never heard more sirens in my life."

Since the people of Oregon went to the polls three years ago when they voted to decriminalize drug use, addiction has soared. The state currently has one of the highest addiction rates in the country. The most revealing indicator is probably the increase in fentanyl overdose deaths, which has increased 1500% since before the pandemic.

The measure did not legalize the use of addictive substances such as fentanyl, methamphetamine or heroin. But it did reduce the consequences, eliminating incarceration and imposing fines of up to $100. That amount could be waived completely if individuals sought treatment to overcome their addiction within days.

That measure also intended to improve social services to treat addiction, using funds generated from taxes on marijuana (which was legalized for recreational use in 2015) and the savings resulting from fewer arrests and incarcerations.

In November 2020, Oregon became the first state to decriminalize drugs. Now in 2024, it is about to become the first to recriminalize them. Although there are voters who still defend the 2020 decision, such as the ACLU, polls show that the measure, which was an important issue on the progressive agenda, is no longer supported by the majority of voters and politicians.

It lost its luster even for those like the state's governor, Tina Kotek, who defines herself as a "progressive Democrat". Just a few months after advocating that the measure had been successful because, at least, it got people talking about addiction, she acknowledged its adverse outcome:

This month she pledged to sign a bill into law to reverse the policy. The bill was introduced by Democrats.

A 180º turn

"Treatment Over Incarceration." 58.46% of the state was in favor of decriminalization. It was sold as a more "humane" approach to the drug problem, claiming it would allow users to get treatment that would free them from methamphetamine, cocaine and fentanyl addictions. According to a local newspaper, the bill read:

"No one wants to see people with addictions in jail or prison because they’re addicted to something," argued Foundation for Drug Policy Solutions President Dr. Kevin Sabet in a recent interview with KOBI-TV. "Unfortunately, Measure 110 had the exact opposite effect." He claims people were misled.

Whether they were deceived or not, most voters in Oregon agree it was a mistake: 56% supported repealing the law late last year, a survey from Emerson College Polling revealed.

Half said Measure 110 had made communities more unsafe, while only 20% said they felt safer. Sixty-four percent preferred to remove the decriminalization portions rather than leave the law as it was.

If ordinary citizens were shifting their stance as months and years passed, uniformed officers were suspicious from the start: "Many officers perceived that M110 is not serving the population most impacted by drug addiction and substance use disorder," according to a study conducted by three researchers at Portland State University which collected testimony from about 20 officers.

Police consulted said the measure made their jobs more difficult. It reduced their ability to detect other crimes. Registering suspected drug possessors allowed them to uncover other offenses. It also helped them to recruit informants. They were able to find dealers by threatening people in possession of drugs.

Most claimed that they had handed out few to no citations. They knew that those who were caught would simply ignore the required fines. In other words, "Not worth the time." They claimed they could provide treatment information without having to dole out fines.

Recovering addicts are against decriminalization

The NGO Oregon Recovers consulted more than 1,200 recovering addicts on decriminalization by mail and social media. Some 83.7% stated that consumption had increased since the penalties were removed. 50.5% believe Measure 110 is the culprit, while 49.5% think it would have happened anyway.

Even though nearly half of the respondents voted in favor of the measure three years ago, today almost 80% think it should be modified (56.1%) or eliminated (23.3%). 83.7% say that "some people need criminal justice or court intervention to motivate them to pursue recovery."

The numbers of the collapse

If the polls aren't enough to prove the law has been unsuccessful, phone records may convince people of the fiasco. An audit by the Oregon Health Authority revealed that only 1% of people cited for substance possession called the hotline set up as part of the program. Those who dialed the Recovery Center Hotline number were spared the fine of up to $100 that came with the citation. "Treatment Over Incarceration": If you call and ask for help, you avoid penalties (financial and jail time). Those cited, however, did not call.

An Emerson College poll indicates that 38% of voters are more likely to vote to decriminalize drug offenses upon learning that information. In its first 15 months, the Recovery Center Hotline took 119 calls. Only 27 people called to inquire about drug-related treatment. Each call cost the state $7,000. The audit concludes, "It is unclear if the M110-specific hotline provides the best value given limited state resources."

Experts and first-hand witnesses claim that those who were supposed to pay a fine and did not call the hotline were not actually prosecuted for ignoring the sanction. The local newspaper OBP proved this. It reported what "police say plays out all too frequently in downtown Portland."

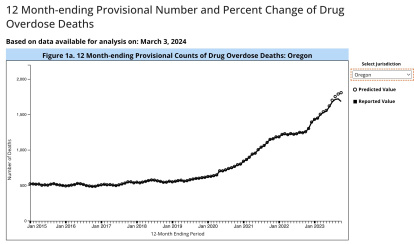

Voz Media reported late last year that overdose deaths had increased thirteen-fold, nearly seven times more than the national average. The CDC's provisional death records show a glimpse into the increase in overdoses:

Número provisional y variación porcentual de muertes por sobredosis de drogas al final de 12 meses. (CDC)

(CDC)

State data shows that from 2019 to 2022, unintentional opioid overdose deaths increased 241%, according to NPR. Fentanyl deaths increased by 1,500% since 2019, according to federal data analyzed by The Oregonian. It is the highest increase in the country.

By 2023, Oregon moved from 36th to 17th out of 39 states in synthetic opioid deaths. That is the equivalent of 30 deaths per 100,000 population.

The public audit of Measure 110's results from early last year also showed that Oregon's Treatment Over Incarceration program ranked 50th in the nation in access to treatment.

Lessons from Oregon

It was called a "model" for other states. They said it was a "victory for common sense," that would be "closely watched as a model for other states." A "historic" vote that "fundamentally transforms the state’s approach to personal drug use and may prove to be a model for future reforms." Back in November 2020, Measure 110 was praised. Three years later, the narrative has changed. Rather than being a model for other states, Oregon has become a nightmare to avoid.

What can be learned from Oregon's mistake? Luke Niforatos, Executive Vice President for the Foundation for Drug Policy Solutions told Voz Media, "Normalising drug use is horrible for a community," "It seems intuitive, yeah." (Despite this, he adds, promotion of the measure was very effective.... "Treatment Over Incarceration.")

"Our perspective is we should not have policies that normalize or encourage drug use," Niforatos said. He believes that is what decriminalization does. "Drug use became normal across the state... people who were smoking fentanyl and injecting heroin on the street were able to legally do so (in a practical sense because legally it was still prohibited)." "Any metric you look at was much, much worse and the public was less safe as a result of Measure 110."

Another lesson from the Oregonian case is that "the average person who is addicted to the various drugs that are on the street is not often going to self-choose to check into treatment." "That usually doesn't happen, because it's such an intense addiction."

It is necessary to create a system, he says, that "pushes" those who are on the verge of addiction or already submerged in its depths into treatment. The police play a crucial role.

People suffering from addiction are in "denial," they are not going to choose treatment for themselves. "We're not going to get out of the crisis by arresting everyone."

"Less than 10% of Americans in this country who had a substance use disorder had access to treatment," he said. "We have to have a partnership of law enforcement and public health to make sure that that happens before more people die before more families get hurt."

"What we learned is the harsh truth of addiction: people need help, people need a handout."

Death to Measure 110. Long live HB 4002?

After more than 1,000 overdoses in three years, state legislators finally took action: 21 senators and 51 congressmen passed a bill to re-criminalize drug possession. The bill had bipartisan support. HB 4002 has been sent to Governor Tina Kotek and is awaiting her signature. Kotek said she will sign the bill into law.

Contrary to what might be expected, the Republican caucus joined a Democratic initiative to pass the bill. It increases possession charges, although it is just as true that Democrats wanted to impose penalties of up to 30 days in jail. After negotiations with the GOP, that number was extended to 180 days, according to local media.

Under the new bill, those charged with possession will face misdemeanor charges. The measure also seeks to facilitate access to treatment. Now that the state has decided to do away with the "Treatment Over Incarceration" program, the effectiveness of reverting to a more conventional model remains uncertain.