Towards Brazilian autocracy

While Lula embraces the worst dictatorships and the STF suppresses dissent, Brazil is moving away from liberal democracy, edging closer to the "catrochavista" model envisioned by Lula and Fidel when they founded the São Paulo Forum in 1990.

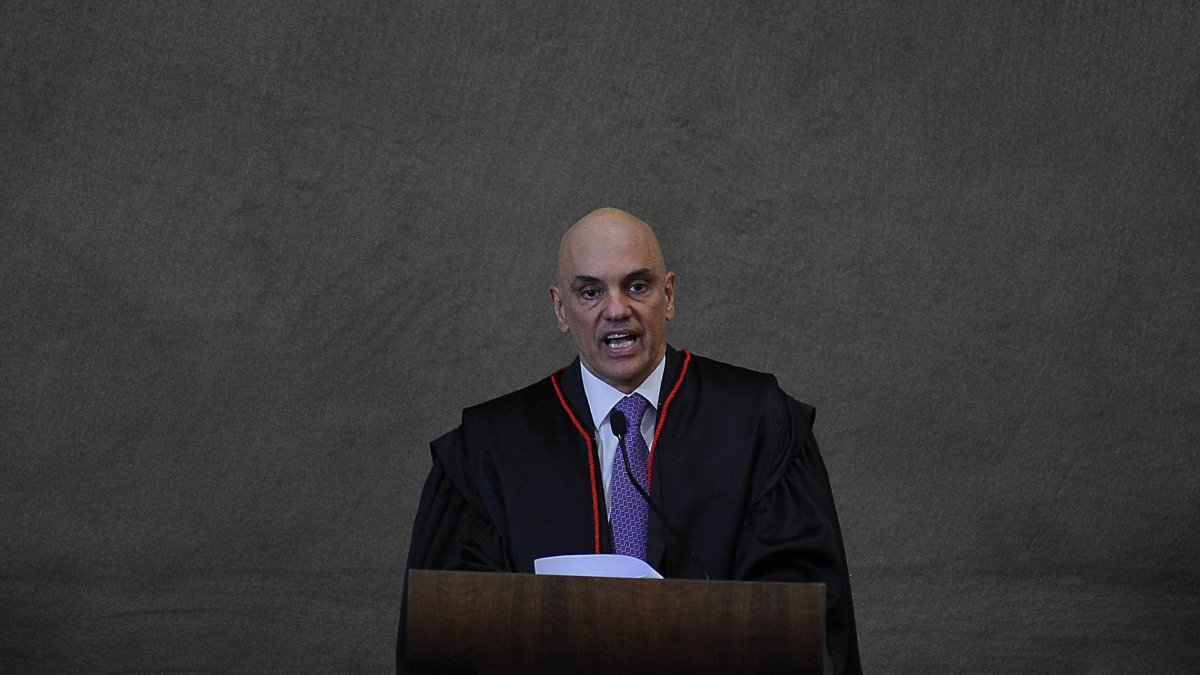

Brazilian judge Alexandre de Moraes

In Brazil, justice seems to have become a political weapon under the leadership of Supreme Federal Court (STF) magistrate Alexandre de Moraes. Moraes, who is leading a series of investigations and judicial measures targeting former president Jair Bolsonaro, his family, and supporters, has sparked controversy. This pattern of persecution began to emerge clearly at the start of Bolsonaro's term in January 2019 and has intensified over time, consolidating a strategy aimed at neutralizing the Brazilian political right.

The strategy includes arrests, searches, and the blocking of bank accounts targeting those who support the former president. On September 7, 2021, Moraes ordered the arrest of two Bolsonaro supporters and the blocking of Pix passwords—a popular electronic payment system in Brazil—along with the bank accounts of the National Association of Soybean Producers (Aprosoja) and its affiliate in Mato Grosso. The justification for these measures was the accusation that these entities were financing demonstrations in support of the president.

Weeks earlier, in late August 2021, Moraes authorized searches of the homes of Congressman Otoni de Paula (PSC-RJ), singer Sérgio Reis, and seven others for calling for Independence Day protests. Earlier still, in February 2021, he ordered the arrest of federal deputy Daniel Silveira (PSL-RJ) after he published a video critical of STF judges. Silveira's defense described this action as an attack on his parliamentary immunity, freedom of expression, and the fundamental principles of the Brazilian criminal process.

These actions are not isolated cases, but appear to reflect a system led by Moraes, who, as president of the Superior Electoral Court (TSE) during the October 2022 elections, played a decisive role in the process that culminated in the victory of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. His influence raises serious concerns about the impartiality of judicial and electoral institutions in Brazil, transforming Justice into an instrument used to stifle political dissent.

The judicial fist of 21st Century Socialism

The use of justice for political purposes is not a new phenomenon, but in Brazil, it takes on a particular aspect under the banner of 21st Century Socialism, an ideology promoted by Lula alongside Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro. This model, which has eroded liberal democracies from within, relies heavily on manipulating the division of powers as a key tool. In this context, Moraes emerges as a crucial ally of Lula, the Workers' Party (PT), and their interests.

Upon assuming his third term in office on January 1, 2023, Lula reopened full relations with dictatorships such as Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua, gestures that reflect his alignment with authoritarian regimes. In May 2023, he received Nicolás Maduro at the Summit of South American Presidents, attempting to rehabilitate him internationally. In July, he hosted the European Union-CELAC Summit to support these autocracies, and in 2024, he traveled to Bolivia to back the regime of Luis Arce. His foreign policy, marked by the strengthening of the BRICS and his openness to China and Iran, highlights a vision that prioritizes alliances with anti-democratic governments over the values of democracy and the republic.

Internally, the judicialization of politics in Brazil is undeniable. Cases like that of Débora dos Santos, sentenced to 14 years in prison in 2023 for writing "Perdeu, Mané" with lipstick on a statue—an act treated as an "attempted coup"—stand in stark contrast to the impunity given to similar desecrations in leftist protests. This selective application of the law mirrors tactics used in Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua, where opposition is silenced under legal pretexts.

Roots of an alliance: Moraes and Lula, a power pact

The relationship between Alexandre de Moraes and Lula has deep roots that trace back to the early 2000s. In 2005, during Lula's first term, Moraes was appointed to the National Council of Justice (CNJ), a position he held until 2007, marking his entry into the orbit of the PT. After a stint as Secretary of Transport in the municipal government of São Paulo (2007-2010) and a brief period in the private sector, he returned to public service in 2014 as Secretary of Public Security of São Paulo under Geraldo Alckmin.

His rise to the national level came in May 2016, when Michel Temer, following the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, appointed him minister of justice. This appointment, made in a government that continued many of the PT's policies and was tainted by the Lava Jato scandal, sparked controversy. In February 2017, after the death of Judge Teori Zavascki—who had been a key investigator of the Petrobras corruption scandal—in a plane crash, Temer nominated Moraes to head the Supreme Federal Court (STF). This decision was ratified by the Senate, despite widespread criticism of its politicization.

The current composition of the STF reflects a leftist influence: of its 11 members, three were appointed by Lula, four by Rousseff, and only two by Bolsonaro, with Moraes completing a court that leans toward the PT.

The relationship between Moraes and Lula was further consolidated after the latter's return to power in 2023. On July 1, 2023, the international press highlighted Lula's decision to appoint Cristiano Zanin, his former lawyer in the Lava Jato case, to a seat on the STF. In February 2024, Ricardo Lewandowski, who had played a pivotal role in overturning Lula's convictions, was appointed Minister of Justice. These appointments appear to strengthen Lula's position, utilizing the STF as a tool for political control and protection.

The rise of the super-powerful Moraes

Moraes' rise to almost absolute power began in March 2019, when the STF, under the presidency of Dias Toffoli, granted itself the authority to open the Fake News Investigation, that arbitrary alibi with which the global left seeks to control freedom of expression. This move allowed the STF to act as victim, prosecutor and judge simultaneously, violating the accusatory system. Moraes, appointed instructor, expanded this indictment to encompass any criticism, taking control of at least eight similar investigations, many focused on Bolsonaro and his allies.

Over time, Moraes amassed extraordinary powers. He ordered raids against individuals who criticized the STF on the internet, forced media outlets like *Crusoé* magazine to retract articles—such as one linking Toffoli to Lava Jato in April 2019—and blocked social media accounts. In 2022, as president of the TSE, he solidified his grip on the electoral process, banning the use of terms like "thief" to describe Lula—despite Lula’s past convictions in Lava Jato—and censoring conservative media outlets like Oeste and Jovem Pan. During the pandemic, Moraes intervened in executive decisions, including blocking Bolsonaro from appointing Alexandre Ramagem as director of the Federal Police, a move that was considered a presidential prerogative.

The STF, supported by the majority of its judges, has become an all-encompassing institution: a constitutional, appellate, and criminal court that handles over 100,000 cases annually. This concentration of power, devoid of time limits or external oversight, has turned Moraes into a "juristcrat" with nearly divine authority, as described by prosecutors like Marcelo Rocha Monteiro and Cleber Tavares Neto. They have criticized investigations like Indagatoria 4.781—launched against Jair Bolsonaro and his supporters—as a "collection of illegalities" and an "Orwellian" process, questioning its origins and the potential violations of the accusatory system.

Examples of these actions include the cases of Daniel Silveira, sentenced to nearly nine years in prison in 2021 for a critical video, and Débora Rodrigues dos Santos, sentenced to 14 years in 2023 for a symbolic protest act. In September 2021, Moraes ordered the detention of the CEO of GETTR, a former advisor to Donald Trump, at Brasília airport after a meeting with Bolsonaro. The episode lasted three hours before the individual was allowed to leave the country. These measures, presented as safeguards for democracy, have been widely criticized for their arbitrary nature, raising concerns internationally about their fairness and legitimacy.

Prosecutor Tavares Neto has warned that Moraes has the power to "convict without a crime, without accusation, and without defense," a troubling assertion that highlights the potential for abuse of judicial power. Moreover, the raids carried out against critics, such as the seven people raided in 2019 whose assets have yet to be returned, remain unresolved, adding to concerns about the fairness of these actions. During the 2022 elections, under Moraes' leadership, the TSE penalized businesses that offered discounts linked to Bolsonaro's party number (22%) and censored an unpublished documentary by Brasil Paralelo about the stabbing of Bolsonaro. These actions, which the leftist establishment defended as measures against "fake news," have sparked criticism for potentially stifling free speech and influencing the political narrative.

The relentless censor: The case against X and the digital war

The confrontation between Moraes and Elon Musk in August 2024 marked a significant turning point in the Brazilian Supreme Court's control over the digital space. Musk's refusal to remove accounts on X, as part of an investigation into "disinformation," led to Moraes shutting down the platform's local offices in Brazil. In response, Moraes imposed heavy fines of up to 50,000 reais per day for using VPNs to bypass the restrictions and froze Starlink accounts to collect penalties totaling 19 million reais. On September 2, 2024, a five-judge panel of the STF upheld Moraes' decision, effectively cementing his role as the "internet sheriff" in Brazil. Musk, one of the world's richest and most influential figures, ultimately yielded to Moraes' demands, and the block was lifted in October 2024. However, this episode attracted global attention, raising concerns about the potential for judicial overreach and the impact on digital freedoms.

Since 2020, Moraes has blocked at least 340 accounts and deleted thousands of posts, according to the New York Times. Media outlets such as Terça Livre and Gazeta do Povo also faced restrictions. In 2022, messages leaked by Folha de Sao Paulo revealed that a deputy of Moraes instructed to "use creativity" to justify actions against Oeste, evidencing an arbitrary approach.

The relentless persecution of Bolsonaro

The persecution of Jair Bolsonaro began shortly after he assumed office in 2019 and intensified following his defeat in the 2022 elections. In addition to investigations into the 2018 TSE document and the arrest of his allies, Moraes authorized police operations in February 2023 that resulted in the confiscation of Bolsonaro's phone and passport, accusing him of plotting a coup. On January 8, 2023, in the wake of riots in Brasília, Moraes oversaw the conviction of 232 individuals and succeeded in disqualifying Bolsonaro from the 2026 elections, a move Bolsonaro has condemned as "political persecution." In response, Bolsonaro’s son, Eduardo Bolsonaro, announced on March 18, 2025, that he would step down from his position and seek justice in the United States, citing threats of arrest.

Shadows over the ballot box

Bolsonaro’s skepticism about the electronic voting system, which Moraes staunchly defends, has garnered international support. Numerous countries, politicians, and experts share doubts about the system. For instance, Germany's Constitutional Court banned the use of electronic machines in 2009, citing concerns over their inability to ensure "a secret ballot and democratic control of the counting process." However, simply questioning the transparency of the system is considered by Moraes as "anti-democratic," leading him to order the removal of accounts that raise such concerns. Moraes' dual role as both an STF judge and president of the TSE in 2022 creates a clear conflict of interest, further eroding trust in the electoral process.

Judicial oppression and global repudiation

Today, Brazil is experiencing a stifling atmosphere, with the STF—described by American journalist Glenn Greenwald as "deeply authoritarian and censorship-obsessed"—transforming dissent into a criminal act. Internationally, figures such as U.S. Congresswoman Maria Elvira Salazar, Senator Rick Scott, and others have called for the revocation of the STF judges' visas in response to these growing concerns: "Judge de Moraes has a well-documented record of restricting freedom of expression, particularly against individuals and groups with conservative political positions. His latest actions represent the culmination of a broader pattern of judicial overreach. We respectfully urge you to deny any application for a U.S. visa or admission to the United States, including revocation of any existing visa, for Justice Alexandre de Moraes and the other members of Brazil's Supreme Court complicit in these anti-democratic practices."

In her website the congresswoman elaborates further on what is currently happening in Brazil: "Brazil not only has as president a criminal convicted of political corruption, Lula da Silva, but now it has a totalitarian operator as the president of the Supreme Federal Court, Alexandre de Moraes." Four Brazilian attorneys general denounced a "appropriation of power" without accountability, and the Economist Intelligence Unit downgraded Brazil to 57th in its Democracy Index 2024 for censorship of X.

The Freedom House 2024 Report highlights that Brazil has seen a decline in its civil liberties score, citing judicial interference and disproportionate restrictions on the press and citizens as key factors contributing to this regression.

The Bolsonaro trial and the democratic decline

On March 26, 2025, the STF unanimously agreed to indict Bolsonaro and seven allies for "attempted coup d'état" in connection with the events of January 8, 2023. Moraes, the rapporteur of the case, stated that there was "reasonable evidence" that Bolsonaro "knew, managed, and discussed" a plan for a coup. The former president now faces up to 40 years in prison and has criticized the impeachment proceedings, claiming that they are advancing "14 times faster than Mensalão and 10 times faster than Lula's Lava Jato," with an "outcome decided in advance."

World

Brazil: Former President Jair Bolsonaro to be tried for ‘attempted coup d'état’

Diane Hernández

The situation in Brazil is dire. Within the context of respecting republican values and human rights, the government's increasingly totalitarian trajectory casts a dark shadow over the future. The core principles of the rule of law, the separation of powers, and transparent elections are under threat, all within the context of a president convicted of corruption, whose rise is supported by a judge consolidating unprecedented power in Brazil’s history.

As Lula aligns with some of the world’s worst dictatorships and the STF (Supreme Federal Court) cracks down on dissent, Brazil appears to be drifting away from its liberal democracy, edging closer to the "catrochavista" model envisioned by Lula and Fidel Castro when they founded the São Paulo Forum in 1990. Many years have passed since then, and numerous countries in the region have witnessed their freedom and prosperity erode under the sway of this insidious alliance.

Brazilian institutions have barely withstood the onslaught of Lula's administrations and their vast corruption networks. But this time is different. This time, Brazil faces a new and lethal weapon: Judge Moraes. The critical question remains: will Brazilian democracy endure, or is it on the brink of becoming yet another autocracy?