What role does the media play in racial tensions? One studies' findings

The study, by Tablet magazine, suggests that "new theories of racial consciousness were adopted that set the stage for the latest riots."

Protesta Black Lives Matter/ Wikimedia Commons

It is no secret to anyone that racial tensions have increased in recent years, and the peak came with the George Floyd murder and its subsequent social impacts. The incident took place in mid-2020, and months later, the magazine Tablet produced a statistical study that analyzed the role of the media in increasing or decreasing these tensions.

The study was published by journalist Zach Goldberg, who sought to discover the relationship, if one existed, between the mass media and the rise of racial discourse in recent years. In particular, it was based on the most popular newspapers in the United States, such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal, among others, such as the Los Angeles Times.

Mass media and racial tensions

According to the author, the woke idealogy "began to take hold at leading liberal media institutions years before the arrival of Donald Trump and, in fact, heavily influenced the journalistic response to the protest movements of recent years and their critique of American society."

To exemplify his point, he showed a graph reflecting the number of times the terms "racist(s)" or "racism" were used in the newspapers mentioned above from 1970 to 2019 and expressed it in percentages. In 2011, these terms accounted for 0.0027% and 0.0029% of all words in The New York Times and The Washington Post, respectively. For 2019, the figure stood at 0.02% for the Times and 0.03% for the Post, an increase of 700% and 1,000%.

The change in the Journal was a bit more moderate. It came a year later compared to the other papers, "suggesting that the center-right Journal appears to react to the rhetorical and ideological trends on race advanced by the two biggest left-leaning newspapers."

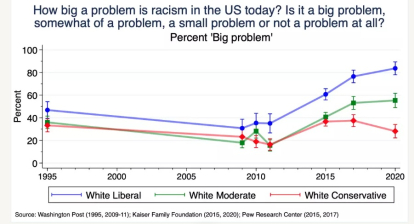

Goldberg also found that, even though segregationist laws were repealed in the mid-20th century, more and more people find racism "a big problem" for the country. In 2011, only 35% of those who perceived themselves as white liberals held this claim, which ended up doubling in subsequent years. Faced with the same question, 61% assured that racism was a "big problem" in 2015, a figure that increased even more in 2017, raising to 77%.

"One possible way of explaining these statistics, is that America experienced an explosion of racism over the past decade and white liberals are uniquely reflective of that change. But another possibility, perhaps more likely, is that ascendant progressive notions about race reflected in a steady drumbeat of reporting and editorializing on the subject from leading national media outlets, encouraged white liberals to label a larger number of behaviors and people as racist," Goldberg reflected.

"In other words, the data suggests not only that more attention has been given to racial disparities, but also that racial disparities themselves are increasingly framed in terms of systemic racism theory. Although this frame is now commonplace, it wasn't so until just a few years ago," he added.

To justify his claims, he drew on the studies of Paul Kellstednt, a political scientist at Brown University, who suggests that changes in racial attitudes follow changes in race-related news content. However, Goldberg clarified that his findings support that the changes were strongest among white Democrats and liberals, weakest for non-white Democrats and liberals, and almost nil for white conservatives and Republicans.

Using a homemade index based on an algorithm originally developed by James Stimson, he found that The New York Times and The Washington Post "are both talking about racial inequality and race-related issues far more frequently than they have since at least 1970 as well as increasingly framing those issues using the terms and jargon associated with 'wokeness.'" He clarified, however, that this does not necessarily mean that his coverage "is causing changes in racial attitudes."

On systemic racism and racial privilege

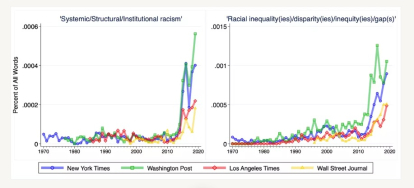

Goldberg addressed these concepts in his study and, again, measured how many times the four major newspapers used them. From 1970 to 2014, the combined frequency of use of the terms "systemic racism," "structural racism," and "institutional racism" never exceeded 0.00006% of all words in any of the four.

However, in 2014 mentions began to multiply. For 2019, the figure in the Times was 0.0004% of all words and 0.00056% in the Post, meaning they used them ten times more than in 2013.

"In other words, the data suggests not only that more attention has been given to racial disparities, but also that racial disparities themselves are increasingly framed in terms of systemic racism theory. Although this frame is now commonplace, it wasn't so until just a few years ago," Goldberg analyzed.

For the term "racial privilege," it found that the Post and Times increased their usage of the words "white" and "racial privilege" by 1,500% and 1,200%, respectively, between 2013 and 2019. In turn, the frequency with which "privilege" shared lexical space with terms such as "white," "color" and "skin" reached a record high.

"In addition, an analysis of latent associations in the Times . . . shows that the word 'color' increasingly appears together in a text passage with words such as 'marginalized/marginalization,' 'vulnerable,' and 'oppressed/oppression,'" he added.

Conclusions

After analyzing the variables, he found that "what the evidence suggests" is that "the major publications not only greatly expanded the definition of racism and actively promoted a more racialized view of U.S. society in a period that began under a black president and during which many indicators showed slow and frustrating, but consistent, racial progress-but they have done so, in part, by normalizing and popularizing the notion of collective "white people's" guilt."

"Of course, there are real inequities in America, some of which are grounded in the legacies of racial discrimination. But visions to transform the country must reflect as complete and accurate a picture of social reality as can possibly be achieved. Steamrolling or suppressing inconvenient facts leaves us with a picture of reality that's likely to be incomplete, erroneous, and consequently, harmful to progress," he concluded.